Know Your Local Waters

Today, more than a million people call Salt Lake County home. In addition to being Utah’s population center, Salt Lake County is also an economic center for the entire Intermountain West. With increasing development, substantial stream alterations, and a population that is expected to reach 1.6 million by the year 2050, the watershed issues in Salt Lake County are complex and evolving.

For the most part, the mountainous areas of the County are uninhabited and forested public lands cover nearly half of Salt Lake County. These undeveloped lands are a great benefit to the health of our watersheds, and streams in most areas of the upper canyons remain in a relatively natural state. Extensive recreation activities in the canyons do, however, contribute to stream impacts, and mining activities (both historic and existing) have severely degraded water quality in localized areas throughout the canyons.

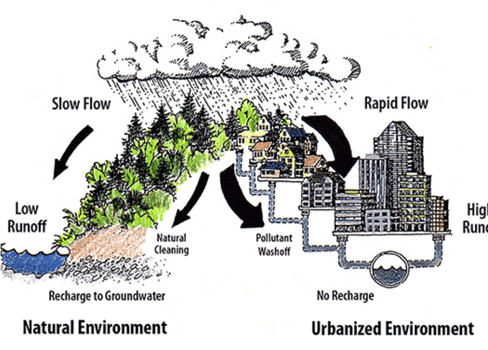

Development has been, and continues to be, concentrated in the foothills and valley floor. In fact, foothills are the zone of greatest urbanization throughout the Intermountain West. As a result, all waterways in these lower elevation areas of Salt Lake County have been degraded to some degree by human activities, some quite dramatically.